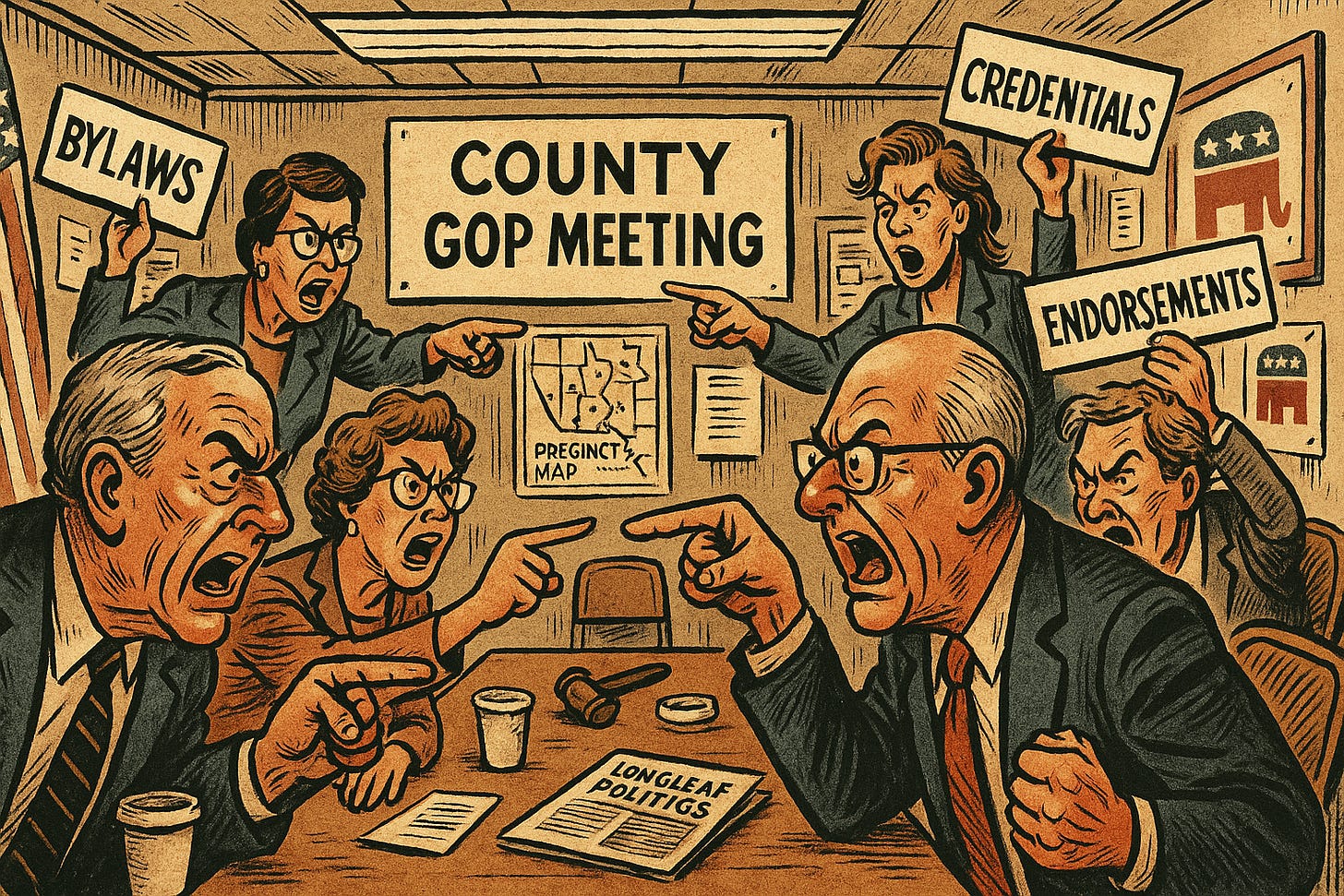

Why county GOP groups have so much drama

County parties are where the movement’s biggest fights get worked out face to face

County politics can really get heated.

Honestly, this shouldn’t be a surprise: When you gather the most committed people in a county and ask them to compete for influence, you’re going to have some dustups.

A lot of the disputes might look unreasonable and silly (and sure, some of them are). But they’re often the result of real differences about mission and strategy.

And sometimes they even comes to blows, as the Cumberland County GOP reminded us last week when two party leaders filed assault charges against each other. I won’t go into all the grisly details (you can read them at CityView if you’d like), but I do want to talk about why county politics can be so contentious, and why it matters1.

Why county parties run hot

I’ve written before that politics is the same at every level. The stakes change, but human nature doesn’t. A U.S. Senate race and an HOA election can look remarkably similar behind the scenes.

County Republican and Democrat groups fall right in a sweet spot for drama: Local enough for disputes to be personal and unavoidable, and important enough for them to make the news.

These county party groups are where the big ideological debates inside political movements writ large get worked out face to face. So the same fights you see playing out on TV or on X over the direction of the party land in cramped quarters.

With proximity comes extra heat. At the national level, there’s a bit of a remove. There’s still plenty of sniping, but it comes from behind a keyboard. That’s not possible for county parties.

Plus, the state party structure forces counties to act as a unit, live and in person. Precincts feed into counties. Counties then feed into districts and the state. You can’t avoid the county step, even if some factions would like to.

County GOP groups operate based on who shows up at key meetings. If you can get a few dozen people to appear in-person when voting happens, you can easily swing the results.

Meanwhile, the stakes are real. County organizations aren’t just idle hobbies. They carry concrete responsibilities that touch elections and governing. To name a few:

Vacancies. In single‑county legislative seats, the GOP executive committee effectively decides a mid‑term replacement.

Elections administration. Parties nominate members to county Boards of Elections and recruit the poll workers and observers who keep sites running smoothly.

Delegate pipeline. Precinct and county meetings elect delegates up to district and state conventions, shaping platforms, officers, and the future bench of candidates.

Ground game. County parties are the ones often out there on the street doing the hard door-to-door work of campaigning.

County party leaders also often become the next state party leaders, or candidates for office themselves. Just look at Michael Whatley, the former state GOP chairman who’s now running for Senate. Or Mark Meadows, who was a county party chairman before being elected to Congress. Or Brian Echevarria, a former Cabarrus County chairman who’s now in the N.C. House.

What I found looking back

All that is theoretical. To make it a bit more real, I read back through a decade of county‑level intraparty dustups in North Carolina to figure out where the friction actually happens.

Admittedly, these are primarily the ones that made the news. They don’t include the much more numerous disputes that live in closed Facebook groups and text chains.

What I found is that these fights often look procedural — over agendas, credentials, who got recognized. But the real disagreement is strategic.

A county party executive committee does not necessarily mirror the county’s Republican electorate. It skews grassroots and red‑meat. That energy is valuable; it also has blind spots. The incentive in the room is to please the most engaged activists. Meanwhile, elected officials often have considerable sway in the room — and they often have different incentives and a broader view of things.

In practice, almost every fight falls into one of two big buckets.

Establishment vs. grassroots

You could describe this in several other ways, too: pragmatism vs. idealism, electability vs. purity, etc.

But this is essentially the argument over purpose: Is the county party primarily a coalition engine designed to win general elections, or a movement steward charged with policing the brand?

Establishment leaders tend to stress electability and big-tent policies. Grassroots activists tend to prioritize ideological clarity and accountability for Republicans they see as drifting.

This often shows up as censure votes, which U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis has faced over the years. In Lee County this spring, Republicans advanced a “disloyalty” resolution aimed at Senate leader Phil Berger over a past judicial endorsement.

But it happens in other ways, too.

The Cumberland County dispute last week is a decent example. It stems from a group of Republican leaders who endorsed a more “electable” unaffiliated candidate for Fayetteville mayor over a Republican candidate who happens to be the father of another county GOP leader.

In Cabarrus County, a county commissioner decided to leave the Republican Party in 2023 over pressure from the county GOP over some of his votes.

Different names, same core question: Are county parties widening the circle to beat Democrats, or tightening it to ensure purity?

In‑group vs. out‑group

This bucket is similar, but it’s less about ideology and more about belonging and control. The lines get blurry sometimes.

For example, the Cabarrus County dispute later morphed into a controversy over appointing a replacement to the commission when Chris Measmer was tapped for the N.C. Senate.

The more deep-red the county, the more likely it is that the disputes are in this bucket rather than the ideological one.

In Macon County in 2023, an insurgent slate quietly organized a county convention takeover that replaced a long‑standing operation overnight.

In Henderson County, something similar played out last spring. A paperwork and seating fight at the county convention turned into a legitimacy war. One side said many precinct leaders weren’t properly seated; the other side said they were and accused the chair team of rewriting rules after the fact. The result: walkouts, competing meetings, and weeks of arguing over who actually runs the county party. It’s less ideology than who gets to decide.

It’s not rare for these flare‑ups to draw law enforcement. Besides the latest Cumberland dustup, the Henderson County dispute resulted in the county chair being charged with assault on a female, according to local reports. Something similar happened in Buncombe shortly before that. And in several counties, tense meetings have ended with escorts out of the room, trespass warnings, or both.

None of that is the norm — but it happens often enough to be a pattern. That’s not because people are uniquely bad here. It’s because the county level is close enough to power to matter and close enough to home to sting.

Not just a Republican phenomenon

A quick note of fairness: Democrats wrestle with the same human dynamics. I focus on the GOP because that’s my concern. There are also simply fewer county Democrat groups that matter. So much of that party is concentrated in a handful of urban areas.

Still, friction on the other side of the aisle sometimes bubbles over, too.

In Mecklenburg County, Democrats argued over internal culture and representation after the county party’s executive director resigned, alleging a racist and hostile environment. Durham’s had similar issues.

In Wake County last year, county Democrats split over endorsements in nominally nonpartisan races, with formal complaints, public letters, and bruised ties to the statewide operation.

The healthier pattern

Heat is not inherently unhealthy. A party needs places where its wings can argue about priorities and standards. Our recent Mecklenburg GOP chair race is a good example.

It was competitive and candid, but orderly. It still got tense — one candidate said misinformation was being spread about him by the other — but there were real policy disagreements on the table. The two candidates had sharply different visions about whether to field candidates in every race or concentrate resources, and whether to invest in a physical headquarters or run lean and mobile.

Even so, credentials were handled cleanly, ballots were counted promptly, concessions were gracious, and everyone went home to get back to work.

That’s the model. Let the competing strategies make their argument, give people a fair vote, then point all that energy toward school boards, courts, and turnout. When the process is credible, even the people who lose feel like they were heard — and they stay in the fight.

Cumberland County can be a reminder, not a template. Drama comes with the territory, but our job is to keep it from becoming the story.

A word to readers

Some of you have asked me to spend more time covering county parties. I’ve been hesitant, for exactly the reasons above. It takes a long time to understand all the background, and play‑by‑play coverage can make the drama worse.

Is it worth it to get involved? The answer is probably yes. I’ll keep looking for the stories that illuminate the mission and the mechanics without feeding the spectacle. Drop me tips if you see something worth writing about.

This article got really long, so I’m going to send it without all the extras I usually do in the newsletter. Go check out longleafpol.com and my X account to read everything else I’ve been up to.

This just scratches the surface. As a long time leader in this party, all & I mean ALL of the drama is due to poor leadership at the NCGOP. It is really that simple! There is no strategy. There are no tactics. No one takes responsibility and therefore no one has accountability.

In 2016 I watched Trump supporters turned away from the Wake County Convention, because they didn’t attend precinct meetings. Years later in that same county, we saw a county chair drain the bank account, take the office furniture and the NCGOP - well they did nothing! Or the NCGOP Central Committee meeting under Whatley when the party secretary literally flipped me off during a meeting with no consequence or when that same secretary used profanity toward another leader, lied and there was no consequence.

I had a front row seat as the NC11 District Chair & as a resident of Henderson County. That county chair followed the direction of the NCGOP General Counsel and leadership and the NCGOP threw him to the wolves! Crazy people that didn’t like the ruling went absolutely nuts over the title of Precinct Chair! It was absurd!

No and I mean NO business could ever function if it was modeled after the NCGOP. How does a convicted pedophile host an annual judicial picnic attended by Whatley, Simmons, Newby, both Bergers, etc?? How does an elected Republican endorse a Democrat with no consequence? How does a state party chair unilaterally decide to pay himself $115k/year with no consequence? How do 3 people implement an RNC rule NEVER used in NC to sway a primary with no consequence?

Why do good people walk away from the party? Well, that answer is an easy one! Why would they stay? The spiritual battle is not with the Democrats, it is within the ranks of the GOP & that is what happens when there is no leadership!

You make a great point that the County level is where abstract political ideology meets one on one personal interaction.

It would be nice, if people engaged in tit for tat accusations and denials of underhandedness could also be in one room, not in a charged public meeting or on social media, and discuss their differences civilly. They may not agree, but I think it would go a long way toward understanding. Always two sides to an issue.